|

Here's the most important thing I learned in 5 years working at a consultancy.

It was hinted at when I became a non-smoker, it slapped me in the face when I became a parent, it was drilled into me when I became a coach and a chaplain, and as a consultant working with executives, it became so far cemented into my understanding that I now take it for granted. It remains true across the board -- for CEOs, salespeople, accountants, administrators, artists, doctors, cashiers, students -- anyone who receives information daily through their senses and is tasked with integrating it into their attitude, outlook, strategy or worldview. It is true for individuals as well as organizations. It is true for teams, tribes and nations. So, today, for whoever needs to hear it: YOU MUST LET GO THE IMAGE OF WHO YOU ARE BEFORE YOU CAN BEGIN THE WORK OF BECOMING SOMEONE NEW. You’re probably thinking, “that’s great, but how.” Here’s the how: You currently have an image or an idea of yourself. Burn it, scream at an empty chair, write it out, sweat it out, but get rid of it until it stops showing up. Then grieve it -- cry, laugh, tell stories about it. “Remember that time I …” In my studies as a chaplain, I learned that before you can affirm, you must deny. Clear the hovel, tear out the weeds, scorch the earth, only then can you till and plant and build. You must say (out loud):

Then, remove those environmental triggers or the people in your life who don't see your potential (the smokers or quicksanders who are angry and jealous that you've left them behind), those who would judge, ridicule, diminish or minimize your efforts to evolve and grow. Surround yourself with those people (and voices) who are succeeding and making the change look easy. Organizationally, this may look like onboarding (or removing) the people who can't grok the new vision. All the while, affirming:

It all begins with screaming out loud for all to hear (and sometimes destroying something).

0 Comments

"Most people do not listen with the intent to understand; they listen with the intent to reply." - Stephen R. Covey SELLING

For as long as I have been around salespeople or sales teams, they have lived by (or been force-fed) the idea that they should listen more than they should speak. The idea is to get the customer talking about their pains and needs. The more a customer talks about their pains, the more they reveal or confirm their emotional experience, including vital details about potential solutions. The more a customer talks about potential solutions, the higher the probability that your solution becomes part of the conversation. The more these words come out of their mouth (and not yours) the more they are involved and included in the act of selling themselves on the idea of your product, service or solution. As Jeffrey Gitomer said, “People don't like to be sold -- but they love to buy.” COACHING The same principle applies in coaching. From life coaching to executive coaching, successful coaches ask questions that get their clients talking about pains, blocks, limiting beliefs and bad habits. Coaches rarely give direct advice. You’ll hardly ever hear a coach say the words “you should.” The more the coaching client speaks, the more they externalize their inner dialogue. The more the client speaks, the more they are involved in “trying on the language.” It’s a principle we see in Motivational Interviewing and “Positive Psychology” coaching. The more the client talks about what doesn’t work, the more a coach can respond with questions like “Is that true?” or “What do you really want?” The more clients speak about things like change, potential, possibility and self-image, the easier it is for them to envision their desired outcome. Once again, feeling the words come out of their own mouth is them trying on these beliefs to see how they feel. The better these beliefs feel, the more the coaching client sells themself the idea of change. FACILITATING I believe we can widen this analogy to include the art of facilitation. Facilitators are also tasked with asking questions (mostly to groups) and waiting for them to respond. The facilitator is in the business of selling – not solutions or ideas, but consensus or alignment. If a facilitator were to present a group with a list of 20 vendors to evaluate, the group would be resentful and inevitably tell the facilitator where to stick his list. However, if the facilitator gently and repeatedly asked the questions, “How many names do we need?” “Who else might we reach out to?” “Who else might we include?” and “Who have we forgotten?” then the group will produce a list of their own. The group is then able to point to the list, feel good about the outcome and agree on the work at hand. THE 80/20 RULE The Pareto Principle (or 80/20 Rule) is named after economist Vilfredo Pareto. It specifies that “80% of consequences come from 20% of the causes,” disrupting what we think we know about inputs and outputs. It is a concept that cuts across many industries and theories of distribution. (As early as 1896, Pareto had observed that 80% of the land in Italy was owned by 20% of the population.) We now regard this as an unwritten law in business and leadership development. Where you exert 20% of your energy (or spend 20% of your time) will yield 80% of your results. It shows up in nutrition and weight loss plans – eat healthy foods 80% of the time, and 20% of the time, treat yourself to a serving of something you love. We see it in relationships – give 80% of your energy to your partner, keep 20% for yourself (and your personal, self-fulfilling activities). We even see it in music production and content creation – spend 20% of your time reading other’s work, listening to reference tracks, etc. and 80% of your time writing or creating your own. There’s no reason to believe the 80/20 Rule isn’t the golden ratio for speaking and listening – in fact (to use another auditory example), if you lower the volume on the background music at any cocktail party to 20%, you leave the perfect amount of headroom for lively conversation. It is an indication of our brain’s ability to filter signal from noise. The same can be applied directly to selling, coaching and facilitation. We should be listening (with the intent to understand) 80% of the time and with the other 20% we should be speaking (with empathy) and asking better questions. The first 30 minutes of any virtual session are critical. It is where you greet your participants at the door, make a first impression, establish necessary ground rules, set the tone, begin to build trust and empathy, and get them familiar with any new technology. Ensuring that your participants have an easy time with this new tech -- before the session begins -- can go a long way to make them feel included and significantly boost their engagement later in the session. Here is how we begin every virtual session when using MURAL as our collaborative workspace. 1. Soundcheck/Set-Up (15 min)

2. Welcome/OARRs (10 min)

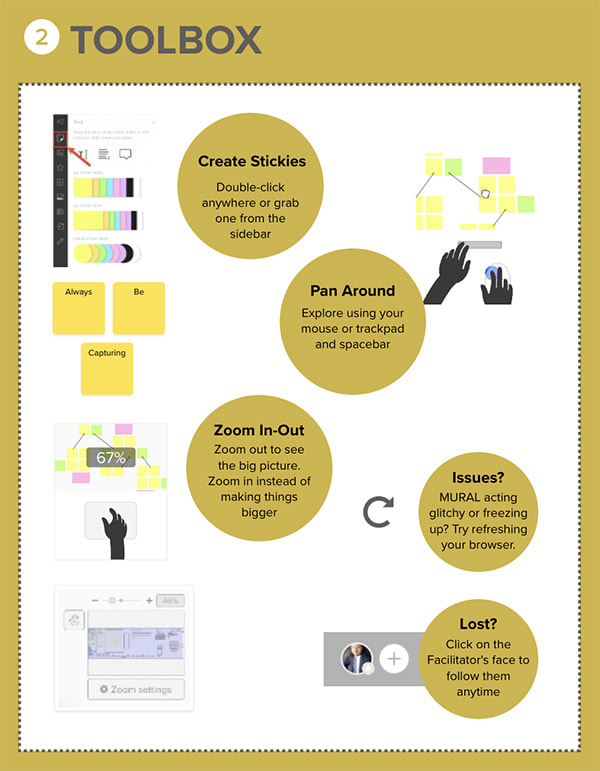

3. Tools Review (5 min)

4. Icebreaker, Check-in (15 min)

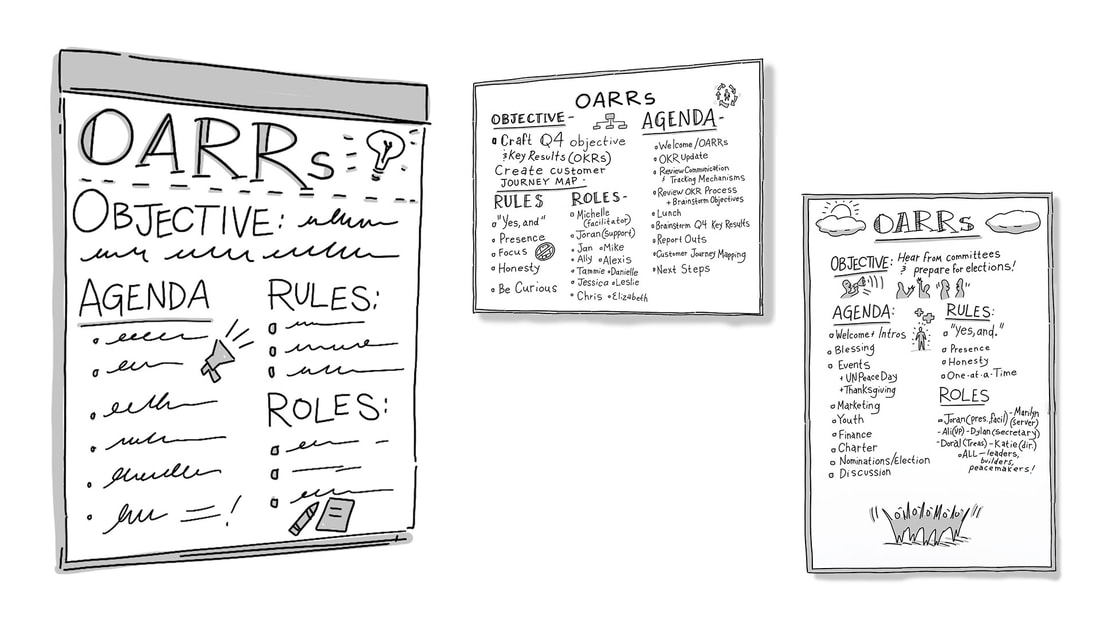

Now, you’re off and running. Finish out your agenda as you normally would. And, if you need help or have any further questions about facilitation, don’t hesitate to contact us at illustri.us. Order Joran's latest book, The Visual Meetings Field Guide: How to Facilitate Great Meetings for Amazing Teams on Amazon or wherever books are sold. We use four key questions to create great meetings. They are called the OARRs (Objective, Agenda, Rules and Roles) and are inspired by our work with The Grove Consultants International.

The OARRs are a sure-fire way to identify your primary objective (“What do we hope to achieve?”), articulate your agenda (“What must we do today?”), get clear on team roles (“Who needs to be in the room and what are they doing?”) and establish some ground rules (“What behaviors do we need to set and reinforce so that we may follow the agenda and achieve our objective?”). 1. What is the Objective for the meeting? Is the meeting to make a decision, share knowledge, explore ideas, or address a challenge? The objective will determine who needs to be there, the length of the meeting, and the right time of day for the meeting. You don’t hold a brainstorming meeting directly after lunch, when the team is full and sluggish. Those meetings are best in the morning when (most) people are open-minded, fresh, and creative. 2. What is the Agenda? To keep everyone focused and to determine the duration of the meeting, you’ll need an agenda. This is a list of all of the business you need to cover or all the decisions you need to make. Consider using a Visual Agenda — either a set of boxes sized according to how much time is spent on each or a Pie Chart Agenda. There are always at least three components to every agenda:

3. What are Our Roles? Based on the Objective and the Agenda, determine who needs to be in the meeting and what their roles are. Roles can be based on a participant’s job description, their expertise, their knowledge of the problem and the marketplace, or their position as a producer or stakeholder. You may assign some roles to people at the outset of the meeting. Who is transcribing or taking notes? Who is acting as a facilitator? Who is keeping track of time and making sure lunch gets ordered? Who is the designated “Devil’s Advocate” — acting as the wrangler of unicorns and asking tough questions about how we might fail? It helps to think about these roles metaphorically. Are you the person driving, coaching, cheerleading, building, etc.? See also: The Five Vital Roles in Any Virtual Meeting 4. What are the Rules? Rules help us cross the finish line as a team. Rules are the covenant and the contract that we abide by as a community. We establish affinity, trust and relationship by mutually agreeing on and following the rules. If your meeting is being held to reach a decision, then your rules need to create a process of decision-making. You might have a rule about deferring new ideas, projects or business to a later date. You might have a rule about withholding judgment, instead asking specific questions that help you arrive at a decision. If you’re establishing an environment of trust, respect, consensus and collaboration, you might have rules about always speaking for yourself (using “I” language), raising your hand, or speaking one-at-a-time. If the meeting is exploratory — designed to share knowledge or brainstorm big, wild ideas — then the rules must support creativity and openness. We borrowed one of the most effective rules for generativity from improv comedy: “Yes, and …” See also: The Power of "Yes, and ..." By invoking the rule of “Yes, and …” we stay positive and build on each other’s thoughts, honoring what everyone has to say. Problem-solving meetings may include the rules “All information is valuable” or “No idea is too small.” You may invoke “Honesty” as a rule, reminding everyone that we will only achieve our goals if we trust one another and respect each other enough to tell the truth. If you don’t want people on their phones or laptops, then invoke the rule of “Focus,” “Presence,” or “All In.” Kindly instruct them that if they need to handle business they can take it out of the room (or turn off their cameras) and return when they’re done. If it’s to be a highly-visual meeting with lots of people sketching or scribing, you may add the rule, “Don’t make fun of others’ drawings.” After reviewing the rules, you may ask, “Are there any rules we forgot?” Allowing the participants to create rules together is a way to ensure commitment and engagement early in the process. |

Details

ABOUT THE AuthorJoran Slane Oppelt is an international speaker, author and consultant with certifications in coaching, storytelling, design thinking and virtual facilitation. Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed